Recently George Brill, an anthropologist from the UK, took Fingerchinder’s pi r2 rings to the Malaysian rainforest on a research expedition to analyse the physiology of the Batek tribe and their

incredible tree-climbing ability—the evolutionary root of our species capacity and desire to climb. Below you can find an insightful extract from his story.

You can find the full report and many more photos at https://www.georgebrill.co.uk/post/back-to-the-trees-of-human-tree-climbing-forgotten-potential-and-skewed-evolutionary-perspective

A Skewed Evolutionary Perspective

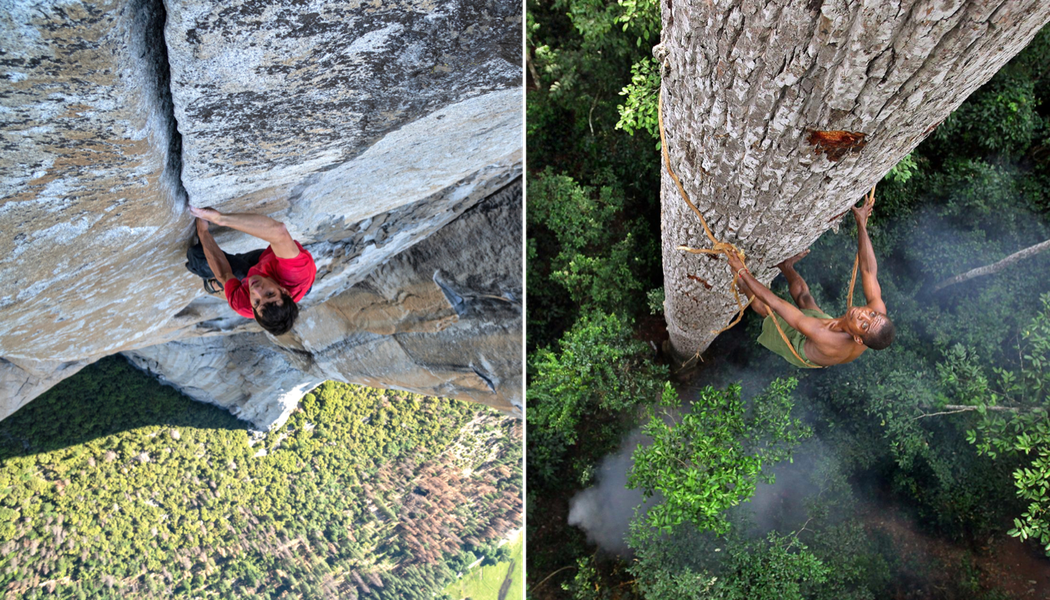

Ever since our human ancestors began walking around on two legs, it has been assumed that we gradually evolved away from our climbing roots. Yet one has only to look at elite performance and the

interest boom in modern rock-climbing globally to realise that perhaps it isn’t that simple.

In fact, around the world rainforest hunter-gatherers exhibit extreme feats of tree-climbing

remarkably akin to those of our cousins—the other great apes. Maintained and passed down for thousands of years, in many of these societies tree-climbing skill holds central economic and social

importance, and represents a vastly under-appreciated form of human diversity, foraging capacity, and locomotor potential.

The Batek tribe of Peninsular Malaysia are one of these tribes—some of the most capable tree-climbers on the planet, climbing to dizzying heights in pursuit of honey, fruit and arboreal

prey.

Over the past two years I have found and gradually grown to know a small group of Batek on the borders of Taman Negara National Park—the oldest rainforest in the world. At the end of 2019 I

returned one final time to analyse their incredible tree-climbing ability first-hand. I watched and examined the Batek move, run and climb for many days, and at long last, with a complete, if

muddled, repertoire of academic literature, direct observational analysis, and personal physical experience, I began to understand what it took to realise our species’ arboreal potential.

The Physiology of the Indigenous Tree-climber

I soon discovered from my personal experiments in tree-climbing—much to the Batek’s amusement—that the level of core and overall body tension required is huge. It is no wonder these individuals

possess such flawless physiques; they are honed and conditioned for a muscular endurance that cannot fail for danger of being unable to return to the ground.

The Batek physique is beneficial also in terms of its leanness. No forager wields unnecessary muscle mass since they don’t have access to the nutritional excess to build it in the manner of

western gym-goers. And yet they are stronger, like gymnasts: pure wiry musculature. And, as any rock climber will tell you, that leanness is a significant advantage. Especially so in

tree-climbing, where, coupled with the Batek’s small stature and hypermobile ankles, it allows them to bring the centre of gravity in close to the tree, even in the layback position of

cheuhtwont.

Hand and foot resilience is another factor, and even after many months of machete handling and walking the jungle barefoot, my hands and feet soon began to rub raw. Batek feet meanwhile are so

leathery that the children don’t even respond to being tickled on the sole!

Perhaps most telling of all, and perhaps also the most obvious, is the general physicality of the Batek. Forged from a life in and amongst the jungle, those that still climb are the ideal in

functional human body composition. They are strong, able to perform well over ten pull-ups untrained, and even hang in excess of thirty seconds on a 24mm edge—something I previously assumed would

be possible only for a rock-climbers abnormally-developed forearms.

Watching the Batek run and climb with their lines of fascia highlighted in kinesiology tape was a true honour and masterclass in human fluidity. Without even understanding the concepts—or perhaps

as a result—the Batek climbers flowed with their artificial kinaesthetic exoskeleton—a picture of elasticity and fluidity in stark contrast to our own paradigms of biomechanical robotics.

Tree-climbing: The Root of Modern Rock-climbing?

As the tree-climbing of old begins to fade from use and memory, I cannot help but wonder on the legacy it represents. Is it simply an ancient tool of relevance only to a select few small-scale

societies? Or does it embody something larger: something rooted deep in the very fabric of humankind.

We might ask, with over eight million individuals a year in the US alone cramming themselves into sweaty boxes to haul themselves up plastic walls, or another however many more million scaling

rock faces around the globe for no purpose at all, only to be lowered before they even reach the top, what is it that we humans see in the art and sport of rock-climbing?

Certainly there is the physical challenge—the satisfaction of problem solving, adventure and testing our limits. And then there is the incredible climbing community that most other sports would

be hard-pressed to get anywhere close to. Yet I can’t help but think that in addition to these points, or rather perhaps through them, modern rock-climbing may simply be the product of an innate

human capacity and satisfaction in overcoming vertical obstacles—a subconscious nod to our ancestral aptitude for arboreal locomotion; a fulfilment of the part of the human psyche designed to

climb trees.

There is no doubt that our species can be far more capable in the trees than is conventionally assumed, and that hidden in the jungles we see a potential that is not dead, nor indeed far from

that of our ape brothers. Yet I wonder: perhaps that potential has never been hidden after all. Perhaps it is possible that across the world we have in fact been developing and exploring that

innate human capacity all along, veiled under a different guise.

The need for food gives way to the thrill of adventure and self-discovery; bare feet against mighty tree-trunks become the friction of fingertips on ancient cliff-faces, and as Alex Honnold

scales the face of Yosemite’s El Capitan for the hundredth time—this time rope-less—perhaps we see re-incarnate the long-refined physiology and unbreakable psychology that was developed millennia

ago in the tree-tops of Africa. Never lost, never replaced: an age-old link to the physicality of our ancestors; a pure freedom and expression of human potential in the wilderness that is our

earth.

Photos by Jimmy Chin (National Geographic); Timothy Allen (BBC)

A Personal Note on the Rings

I know that Jakob will be loath to post this on the website, but I insist that he does. I write this entirely genuinely and it deserves to be added to the article.

I cannot thank Jakob enough for sending me out with a pair of Fingerschinder’s pi r2 rings. They proved invaluable during the research as a multifunctional tool for assessing many aspects of

upper body and finger strength. Since the research was undertaken in such a difficult and, to some extent remote, setting, being able to bring just a single integrated tool was incredibly

advantageous. The Batek loved the rings and spent many hours playing on them during the course of my time there! It is also notable how well the rings held up to the intense humidity and abuse of

the expedition—they are a beautiful piece of craftsmanship and as hardy as anything.

George Brill is an anthropologist specialising in human movement performance. This has led him to spend time with elite athletes and indigenous tribes around the world. You can follow his work at www.georgebrill.co.uk or on Instagram at @georgebrill_

Write a comment